Earlier this week, I checked out an unusual intersection: two punk-hardcore activists were lecturing to 75+ teenagers at a Los Angeles university.  But this wasn’t music camp. Rather, this was the last day of a college prep summer program,  hosted at USC for low-income and first-generation youth. Amazingly, the message stayed clear of “stay in school,†and focused instead on do-it-yourself (DIY) passion and activism. There are implications for our research group.

hosted at USC for low-income and first-generation youth. Amazingly, the message stayed clear of “stay in school,†and focused instead on do-it-yourself (DIY) passion and activism. There are implications for our research group.

Perhaps most importantly, the occasion underscored the “intersection dilemmaâ€: how do learning institutions interface with civic sub-cultures (from punk activists, to the Harry Potter Alliance and Invisible Children)? For me, this intersection is a goldmine – a space of real drama, where subcultures put on a public face, and where institutions give uncertain attention to these emerging civic modes.

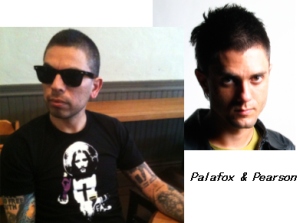

Of course, the actual people matter enormously. Justin Pearson and Jose Palafox (see above) are not your typical punk figures. While Pearson never graduated college, he and Palafox have been key players in DIY hardcore-punk since the mid 90s. They have been in countless bands – see, for example, this Swing Kids video with Pearson singing, and with Palafox on drums.

The activism of Pearson and Palafox is DIY, set against the punk subculture. As friends and independently, their bands have supported organizations ranging from Planned Parenthood, to PETA and the Black Panther Party. Palafox has made documentaries of the U.S.-Mexico border. Pearson just released his autobiography, and was on Jerry Springer with a hoax involving bisexuality.

Very briefly, I want to examine Pearson and Palafox as a kind of baseline for our research. Their example is valuable for its simplicity: compared to our current case studies, they do not have a fantasy content world (e.g., as compared to the Harry Potter fans); and second, the pair presented as individuals — without an organizational apparatus (such as the Harry Potter Alliance).

Yet Pearson and Palafox are intimately connected to DIY culture and activism. For them, DIY is both a cultural stance, and part of their message to the students. “We’re not [expletive] Green Day,†they reiterate to the student audience. Green Day may sell punk music, and tackle social justice — after all, Green Day has a mainstream protest album — but as Pearson decried, “they appeal to the lowest common denominator.”

Which brings us to the first interface — between sub-communities. When Pearson speaks, he proactively tells the students who his group is not. His discourse positions DIY punk as skeptical of mainstream (consumer) music, and distinctive in part because they take true artistic risk.

My ears pick up at Pearson’s boundary claims. In the classroom, this emotion about boundaries feels risky, despite the fact that public schools have cliques and subcultures aplenty. Of course, we have known for decades that boundaries are critically important. Our notion of group cohesiveness, for example, relies on community boundaries defining “who is in and who is out†(McMillan & Chavis, 1986). But the environment of the classroom tends to sideline the emphasis on difference. This makes sense on an operational level, since things just run more smoothly when students can be treated as interchangeable parts, moving identically from grade to grade. And philosophically, universal inclusion is central to schools’ mission to prepare all democratic citizens.

So why invite Pearson and Palafox? Their membership in the punk-hardcore community made them an interesting story (for this blog entry too!), but that wasn’t the central message. Rather, it was their DIY ethic, which celebrates the ordinary person, promising these students that if they are self-reliant and proactive learners, they can each become experts in their own right. Pearson and Palafox introduced this DIY ethic as broadly relevant – i.e., not tied to their own roots in punk culture, which has a strong DIY core.  (And to me, this disassociating of the DIY ethic from culture is a bit dangerous, given how many DIY moments have been commercialized – from amateur radio, to home movie production, to the ancient printing press.) And so I begin to see how much easier it is for a learning institution to seize on DIY culture, but keep participatory cultures a bit more distant, like histories or interesting stories, but not active in their classrooms.

There’s another layer to this story: Stefani Relles. She’s the exception, the amazing educator/writer/scholar who invited Pearson and Palafox. It turns out she’s also immersed in DIY, hosting workshops on Shepard Fairey and the like.

What surprised me is that Relles didn’t just know Pearson and Palafox previously – she described them as part of a broader “DIY culture,†where punk-hardcore was only one element. She portrayed a remarkable diversity in this culture, with “seamless interaction†between those with GEDs and PhDs – doing poetry readings in living rooms, zines, you name it.

As an educator, Relles described the need to build trust on two fronts: both with the artists, many of whom were uncomfortable in classroom settings, and with the funders/administrators, who needed convincing that DIY punks were important for a college access writing program.

Did it work? Many of the students found the presentation inspiring, and declared their intention to stay connected with Pearson and Palafox (check out the video interviews that Relles put up afterward). For Relles as a writing teacher, this serves a core need: writing skills are one thing, but “it’s hard to write anything unless you have personal beliefs.”

For me, this story is just beginning — the event boundaries raise several questions for our research:

- Can the DIY ethic provide schools (or libraries) with a neutral ground to host participatory communities? Do we need stronger theoretical explanations for how this ethic relates to participatory cultures?

- How is this school interface similar to more youth-led efforts, such as the formation of a new Invisible Children chapter at a high school? What are the various adult roles – from mentor, to administrative liaison, to host?

- How can educators create palatable and effective bridges to the participant trajectories within such communities? (Ito et al. delineated hanging out/messing around/geeking out as sequential domains – but it’s not clear how guest speakers like Pearson and Palafox align with these domain boundaries. Even when an institution has dedicated participatory spaces, such as the You Media project in the Chicago Public Library, there are few established models for how to introduce new communities from the outside.)

- When communities shift gears, and tackle civic engagement – including in more public spaces like schools, how does their “public face†begin to differ from the image they portray to members?  Is this a useful place for researchers to study the dynamics of communities in transition?

Frankly, I suspect there are many more questions buried here. I hope to use this blog post as a starting point to future conversations with others in DIY and activist communities – and with our own research group. Comments and correspondence are always appreciated.

————–

REFERENCES:

- McMillan, D. W., & Chavis, D. M. (1986). Sense of community: A definition and theory. Journal of Community Psychology, 14, 6-23.

SEE ALSO:

- Videos of Pearson and Palafox speaking to the students are now online as part of Relles’ YouTube channel

- Details on the SummerTIME program, which is hosted by USC’s Center for Higher Education Policy Analysis (CHEPA)

- Wikipedia entries for Justin_Pearson and Jose_Palafox

- The image at top is based on photos at Pearson and Palafox’s booking agency.

USC’s Center for Higher Education Policy Analysis