Liminal political spaces— Thoughts on my (mediated) attendance of President Obama’s visit to USC and what it can teach us about participatory politics

Neta Kligler-Vilenchik

Â

During the last week, a popular conversation topic on the USC campus was the upcoming visit of President Obama. His visit was planned as part of a political rally, promoting voting for the Democrats in the upcoming California election. Interestingly enough, though, it seemed that a lot of the conversation revolved around the logistics of this visit. People wondered whether classes and events would be rescheduled, how crazy traffic and parking will be. When trying to probe with some of my classmates whether they were planning to attend the rally, most replied that it would be too much of a hassle to come to campus.

Throughout this week I was deliberating on whether or not to attend the rally. As a non-American citizen, I cannot vote in the upcoming elections. Still, I can’t deny the attraction of potentially seeing an American president in real life, and not only an American president – one that seemed particularly endowed with a celebrity quality. Still, I too was worried about the logistics on campus, and – as a busy graduate student – was also anxious about missing too much precious work time. As a compromise, I decided to come to campus, but to arrive only shortly before Obama’s expected speech (hours after first attendees showed up), and to see how things go. In fact, they went much easier than expected, and I arrived at campus rather quickly.

Upon my arrival, I was at first surprised at how deserted the campus seemed. Getting closer to the area of the rally, I found that it was walled off with a large green fence, but a “jumbotron†– a large video screen – was projecting the rally onto the grassy area at the nearby Leavey library, where some students were sitting and watching. In the beginning, I still made several attempts to go into the actual rally. The entrance area to the rally at first seemed encouragingly empty, but then I found out that people had to first stand in a different line to get a ticket. I hung around that area for a while, hoping that somehow I would get in anyway, but it seemed that these tickets were necessary, and the line for it was just too long. The people in charge were warning students in line that they may not get in at time to see Obama’s speech, and their best bet would be to watch the event from the jumbotron. So this was what I did too – I sat on the grass on a sunny afternoon, leaned on a tree, nibbled on a bagel, and watched the President of the United States on the screen, just 50 feet away from me. It turned out to be a unique experience. Not, as I first hoped, because of seeing a president in person in a political rally, but through thinking of the unique characteristics of the perspective from which I viewed the event – that of the “jumbotron†crowd.

Comparing the experience of attending a public event versus watching its mediated version is not new, of course. As early as 1951, the sociologists Kurt and Gladys Lang attempted to compare the experience of attending the “MacArthur Day†parade and watching its televised counterpart. They found that while the audience actually attending the event experienced it as dull and disappointing, when televised it seemed like a dramatic, exciting event. Lang & Lang attributed this gap to the practices of television, which structured the event according to its assumptions of the audiences’ expectations. They called this the “unwitting bias†of television.

Sitting and watching the Obama rally off the jumbotron while sitting on the grass with other students can’t be put on either side of Lang & Lang’s spectrum. It wasn’t sitting at home, watching an account of the rally produced by commercial mass television, using different angles and perspectives. But it wasn’t the same experience as actually attending the rally, either. I was very close to the physical location of the rally, I had other people around me, yet the fence separating this viewing area from the actually rally served as a significant boundary. In this way, the grass on which I sat, together with other students, watching the screening of the rally, can be thought of as a  liminal political space, a blurry boundary zone between the world and politics and the “everydayâ€. Neither watching from at home, nor “being thereâ€, it took on some of the characteristics of its counterparts, creating its own unique experience for its dispersed crowd.

On the one hand, we—the “jumbotron†crowd—were barely 50 feet from the area were the rally was taking place, and where Obama would soon speak. On the other hand, separated from the rally by a large green fence, the “feel†of the experience was palpably different. Whereas inside the political rally, people could not go in with backpacks, food or drink, on the grass of Leavey the atmosphere closer resembled that of a picnic. The audience, mostly USC students but also other guests, were sprawled on the grass in the surprising afternoon warmth (after a chilly morning and a rainy week), looking in the general direction of the jumbotron, shading their eyes from the sun. Some were sitting on picnic chairs, one student had his shirt off. People were snacking on sandwiches and drinks. Some students, perhaps—like me—anxious about the work time they’re missing, were working on their laptops or reading academic articles. The atmosphere, similarly to that felt inside the rally, was that of waiting for “the big event†– President Obama’s speech. But in the meantime, the mood was that of a relaxed afternoon in the sun. The many political figures that appeared in the rally before Obama, and on our screen, were met with relative indifference. A possible cause, or perhaps reflection, of this indifference, was the uncertainty of some of the audience as to what this event was actually about. After a series of Democratic candidates came on stage one after the other and called the crowd to vote for the Democrats, I overheard a student next to me ask his friend: “So is this a Democratic event?â€. His friend wasn’t sure.

The strange quality of our liminal political space was perhaps most apparent during the pledge of allegiance and the national anthem. Looking around me, I could see people wondering, do I stand up or not? Do I say out loud the pledge of allegiance? Do I sing the anthem? Again, the boundaries were blurred. The national ritual was enacted in front of us on the screen, and in very close proximity to us in reality. But we were not really participants in the rally, were we? It seemed that for most, the compromise was to stand up, some said the pledge of allegiance, but only few sang the anthem. Others, however, remained quite serenely sitting down and chatting, or walking across the grass during the singing of the anthem – behaviors that would have most likely been inappropriate within the parameters of the rally. For me, this was quite a relief – I do not know the words of the anthem, and as non-American citizen, am not sure I would feel comfortable singing it even if I would. Standing in front of the screen, I wasn’t as anxious of this as I may have been inside the perimeters of the rally.

President Obama at USC, 10/22/2010, photo by Shotgun Spratling, Neon Tommy

After several more speeches, the moment we had all waited for had come – President Obama came to the stage. He was met with enthusiasm – though perhaps less than I had expected. We, the jumbotron crowd, clapped as well, and the excitement was heightened. Obama began his speech talking about Trojan pride and gesturing ‘fight on’ – which was of course greatly cheered by the USC crowd. During his actual speech, though, a strange anti-climax seemed to occur. The audience gathered around the screen had obviously been waiting for Obama’s arrival. And yet, two or three minutes into his speech, when he began addressing politics, the excitement around me very quickly waned. Some people were chatting with their neighbors, others standing up and leaving. The group of students next to me – those who wondered whether this is a Democratic rally – were deliberating whether to get up and leave, probably in order to avoid the heavy traffic when the rally was over. One of them told his friend: “We waited until now, might as well wait till it’s overâ€. Deciding to stick around for now, they listened to the speech, throwing occasional joking remarks. When the Obama’s speech was over, the crowd quickly dispersed, hoping to reach their cars before all the rally attendees (I know I did…). On their way out, some took pictures in front of the jumbatron. I sure wish I would have taken one – but at that point I didn’t think of this blog yet.

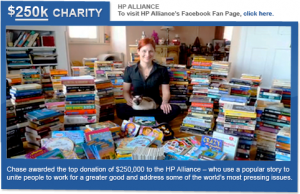

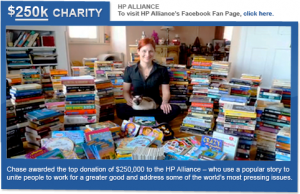

The notion I would like to devote some attention to, then, is that of the liminal political space. Watching the rally off the jumbatron, just a few feet away from the rally, created a unique experience, one different both from actually “being there†at the rally, but also from watching it on television (or the web) or not watching it at all. Rather than thinking only about this event, though, I want to see whether concept of liminal political spaces, and my experiences in this particular example of it, can help us elucidate the phenomenon we’re interested in our research group: that of participatory politics, or the ways in which participatory culture can lead to political engagement. Using the Harry Potter Alliance as one of our key case studies, we are asking ourselves how groups can engage young people in the political process in non-traditional means, building on existing content worlds and fan networks.

Liminal political spaces, as I define them here, are spaces of ‘in-between’: in between politics and people’s every-day lives. These are spaces that relate to traditional political spaces, but yet are uniquely distinct from them. Thinking of my experience at the rally, I’d like to mention several possible advantages of liminal political spaces in terms of increasing participation in democracy.

Crowd waiting in line for the rally (not for the jumbotron…). Photo by Jennifer Schultz, courtesy of NeonTommy.

First, liminal political spaces enable much easier access, or in the political science lingo, reduce the costs of political participation. Those who wanted to attend the political rally had to arrive very early, wait excruciating hours in line, stand all day in the sun without food or drink. Some even waited in line from 3:30 am. On the other hand, I, like many of the “jumbotron†crowd, arrived only an hour before Obama came on. When it was over, we left to our cars quickly, and weren’t stuck in traffic. We managed to experience a presidential visit (more or less), with minimum hassle involved.

Second, they allow for a wider variety of people to participate. For example, Republicans would have probably not felt very comfortable inside the rally, which was very clearly partisan. In our liminal political space, some of the audience criticized Obama or joked about his speech – but they still listened to it, were still part of the experience. They too, then, heard countless reminders of the importance of voting in the upcoming election – though perhaps they took it as a reminder to vote for the “other sideâ€. For me, as a non-American citizen, participation in the liminal political space was more comfortable for other reasons. Not being inside the actually rally, I felt more legitimate in my “outsider†status, where it was ok not to sing the anthem. Around me I saw many who seemed like international students, and I suspect some of them felt the same – wanting to get the experience, but not feeling enough belonging to be inside the rally.

In that way, liminal political spaces allow for participation “on your own termsâ€. We could “participate†in a political rally while sitting on the grass in the sunshine, munching on bagels and chatting. But we still felt like we’re a part of the experience (even if a marginal part).

It seems to me that many of these advantages can be applied to some of the case studies we’re thinking of. Let’s take the Harry Potter Alliance. In many ways, it enables youth an easier access to politics (widely defined). While the view of all youth as being alienated from party politics is an overgeneralization, it does seem to have a point. For many young people, volunteering to take an active part in politics may just be too disconnected from their daily lives. Participatory politics can help bridge this gap, by using current areas of interest as points of connection between the audience and the politics. For example, for a Harry Potter fan, attending a wizard rock concert that is dedicated to fighting for marriage equality is a much smaller leap than attending a traditional political demonstration. Participatory politics furthermore allows political participation on young people’s own terms. The forms of engagement we see in the Harry Potter Alliance vary from raising money, signing online petitions, donating books, participating in beach clean-ups, and encouraging other young people to register to vote (no matter to which party). There are different levels of membership possible, different levels of engagement. Some volunteer 20 hours a week, some sign an online petition once a month. In that way, participation can be diversified, allowing those with different views and different motivations to be a part of the political process, and to define this part for themselves.

On the other hand, the green fence separating our grassy area from the rally has tangible consequences. As liminal political spaces are distinct from traditional political spaces, we must also consider some of their weaknesses, or even dangers, from the point of view of democracy.

A main problem seems to be lower accountability. For the jumbotron crowd, our participation was made on our own terms, but this also meant that we felt much less committed to the political cause. The aim of the political rally was to get people (or, more specifically, Democrats) active and energized towards the upcoming election. They called people first and foremost to vote, but also possibly to volunteer to “make phone calls and knock on doors†(just as a side-note, what year are they living in? have they not heard of social networks?). But our liminal political space just did not seem to have the same energy that fosters active political engagement. The jumbotron crowd heard the same messages but, without the energy of hearing it together with a mass audience in a rally, the effect just didn’t seem the same. Here, it seems that the opposite happened than for Lang & Lang. From what it seems from random interviews, it seems that participating in the rally was a much stronger political-emotional experience than watching off the jumbotron.

Here, I don’t want to be too quick to make comparisons to participatory politics. In fact, in some cases accountability may be even higher than in traditional politics. The Harry Potter Alliance, for example, functions through a structure of chapters and houses, competing with each other on achieving their social causes. Connected through their shared interests, members in participatory politics may feel more—and not less—of a shared responsibility towards their shared social causes.

Another possible challenge, however, is that of the illusion of participation. This may be the argument of many critics about experiences such as our jumbotroned rally: You felt as though you were participating, but in fact you were not contributing to actual politics in any meaningful way. For example, we probably weren’t counted in the number of attendees. Did our attendance still matter politically, if we were not necessarily affected by its political messages? Then again, how does attending the rally matter?

In participatory politics there may be a similar danger. As some critics claim, while young people today are socially active in many ways, they are not involved in traditional politics and, for them, this is the politics that matters. According to their claim, party politics is how US democracy works. In order to make a political difference, you have to play the political game.

Yet the advantages of participatory politics as liminal political spaces can be thought of in several ways.

First, they can be thought of as a step towards engaging with “real politicsâ€. Watching the rally off the jumbotron, for me, still carried with it some feeling of disappointment, that I wasn’t really there. That perhaps next time I will take the extra effort, come early, wait hours in line, and have the “real experienceâ€. Similarly, experiencing politics, even very widely defined, through the “safe spaces†of organizations such as the Harry Potter Alliance has lead some members to think of a future in politics, even if they view politics as dirty business.

But moreover, it seems we should value liminal political spaces for what they are, not only as a step in a trajectory. Counter to traditional notions that see such participation as trivial, we can think of ways in which it is in fact more meaningful to its participants than traditional politics can be. The political rally which we watched on the screen was mostly geared towards increasing political enthusiasm. This is one thing that organizations such as the Harry Potter Alliance definitely succeed in. By linking social causes to narratives, characters and content worlds which their audiences already feel strongly about, these groups manage to recruit fantasy worlds to the causes of current day politics, achieving some spectacular results. Traditional politics can still learn a lesson or two from these liminal political spaces.

The Harry Potter Alliance winning $250,000 in the Chase Community Giving action, achieved by receiving a top number of votes by members.